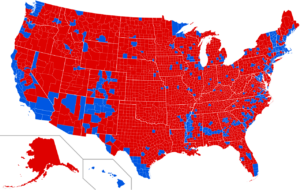

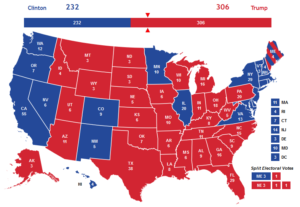

There’s been a lot of talk for most of November (and now into December) about the recent Presidential election. Hillary Clinton lost the Electoral College vote by a considerable margin, 306-232, the biggest defeat for a Democrat since 1988. And yet, her raw vote total (the so-called “popular vote”) currently stands at 64 million and climbing. Her opponent, billionaire real estate mogul Donald Trump, has so-far netted about 62 million votes. And yet, despite 2 million fewer people voting for him, it will be Trump—not Clinton—who takes the oath of office and assumes the Presidency on January 20th.

That doesn’t seem very democratic. So for those who perhaps have never considered the subject carefully, let me offer a few thoughts on the subject, starting with the most important thing that needs to be understood about the United States of America:

The United States of America is not a democracy.

Though that is not politically correct to state, even by some REPUBLICans, it is absolutely true. The US is not a democracy, and calling her one is a terrible misnomer. In fact, one can not find, in either of our nation’s most precious founding documents (The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States) any reference to the USA as a “democracy.” Are there elements of the democratic process at work in the US? Obviously, but that doesn’t make the country a democracy any more than it would the United Kingdom.

As a matter of fact, the founders (by their own admissions in speech and letter) despised, distrusted, and disapproved of pure democracies. The idea of a simple majority ruling over the minority was precisely what they hoped to be freed from in their war against British rule.

The founding fathers of the US often spoke, during the drafting and ratifying of the Constitution, of “The Tyranny of the Majority.” In other words, the idea that 51% could lord over 49% in all matters was a terrifying prospect that they believed would “end in that nation’s suicide” (John Adams, 1814). They feared a simple democracy would ensure a nation’s “short life and violent death” (James Madison, Federalist #10).

The system of Government they adopted to balance efficiency and fairness with the will of the people was instead chosen to be a “democratic-republic” of representative governance. But before continuing, a proper foundation must be established.

America is not a nation of 300 million citizens. She is a union of 50 independent states, each with their own body of citizens, republically-elected legislatures and executives. These states have their own laws, regulations, cultures, traditions, influences, demographics, etc. Each of these states are “united” with 49 other states by a Constitution of shared interests and laws. These states are “united” under a federal government that ensures the drafting of laws which concern all states (and therefore those states’ citizens), the judging of those laws’ Constitutionality, and the execution of those laws with respect to the Constitution.

Those three functions are handled by three separate yet mutually authoritative branches of government. The Legislative branch drafts the laws, the Judicial branch validates the laws, and the Executive branch carries out the laws in the form of policy.

The courts’ judges that make up the federal bench are appointed by the executive and approved by the legislative (thus, a balance of power).

The members of the legislative branch are composed of representatives from each of the states. It is divided into two parts (or chambers). The House of Representatives, of which each “Rep” is elected as spokesperson for his district (a partition of land in his state), and The Senate which, until the turn of the 20th century was composed of men selected by each states’ legislature.

The wisdom in federal senators being selected by state legislatures makes sense, considering it is the role of the US Senate to do the duty of the states, and it is the role of the US House of Reps to do the duty of the districts. And though the districts are within the state, they do not always have shared interests. The bicameral legislature was a brilliant (one of many) compromise by the founders in order to ensure the needs of the individual citizen (the House) and states (the Senate) each had equal yet distinct voices in the federal legislative process. Since the passage of the 17th amendment (but not because of it; more on that later), however, that distinction has been lost and the only real difference in the people between the two chambers is the length of term (2 years vs. 6 years).

As for the executive branch, the founders again concocted a brilliant (one of many) solution to the problems at hand. The primary problem was how to balance the will of the majority of people, without consistently disenfranchising the will of the major-minority (the 49%). Though it is derided today (and often totally misunderstood in its concept, reason for being, execution, and ramifications), the Electoral College was viewed by our founding fathers as their greatest idea, and best solution to their potentially biggest problem.

Most of the criticism leveled against the electoral college stems from an improper view of the American electorate. This is understandable (though not excusable) considering the uniqueness of the states has been de-emphasized over the years, as the power of the federal government has grown (first under Adams, then Jackson, then Lincoln, then Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt, then LBJ, then Nixon, then W. Bush, then Obama).

Furthermore, the lines of distinction between the states has been blurred to the point that many Americans view our nation as a collection of 300 million citizens with 50 partitions, and not (as intended) as 50 states of citizens united under a federal umbrella. Remember that the Founders had a vision for a united group of individual states. In that case, there needed to be a way to elect a person to “preside” over that union in a way that was fair to the (very different) states of the union.

So, how to elect the President?

Well first, what is the President? He is the chief executive of the federal government. He is the CEO of the union of the states, appointed to serve in four year terms and originally limited to serving as bill-signer or vetoer and Chief Commander of our military. Originally he was envisioned as a figurehead; the public face of the nation to those abroad. In many ways it was the most maligned office to the very ones who drafted the job description, since they originally gave the office holder very little real power (naturally, considering their distrust of the English Crown).

But how should the office holder be selected? A simple popular vote election was instantly rejected. A person seeking the office would only need to appeal to the “big states” of Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Virginia, while the “small states” of New Jersey, Delaware and New Hampshire would be largely ignored. A system was needed where each of the small states could have a “more equal” role in selecting their CEO, while still respecting the fact that the larger states had more people.

Remember that the founders looked at America as a union of very different independent government bodies (states), which each had to work together to elect their federal CEO. The idea of a simple 51% winner would have been considered with as much sincerity as giving up and going back to the defeated King George III. It didn’t matter that Pennsylvania had all the population of all the “small states” combined. Oh sure it mattered to Pennsylvania (and to her delegates at the Constitutional Convention), who would have loved a “majority rules” system. But these brilliant men knew that such a system would never be ratified by the smaller states and thus the union would collapse, ready to be invaded by an emboldened England at a later date.

So, as a compromise, the Electoral College was imagined. The system allows for larger populated states to have a larger role in the election of the President, but not to the point of disenfranchising the less-populated states. Likewise it allows the “small” states to cast a loud voice in the choice for CEO, but not to the extent that the minority is ruling the majority.

A state’s Electoral College “number” (in the form of “electors” who by and large cast a symbolic vote…more on this later) is determined based on the number of representatives she has. Her two Senators plus the number of Reps determines the EC#. The state of Arkansas, for an example, has her two Senators plus four representatives for a total of six electoral votes (Arkansas, in other words, has 1/45th of a say in who should be President; California, with its 55 votes, gets 1/5th of a say since it is a more populous state).

In order for a candidate to win the Presidency he must win a majority of the United States’ electoral votes. In order to do that, he must run a nation-wide campaign, one that is appealing to a plurality of states (taking into account their various cultures, traditions, interests, etc). The weakness of a mere popular vote election would limit the campaigning (in 2016, for an example) to the New England area (25% of the USA’s population) and the handful of key/large cities west of the colonies (Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles), which is precisely what the founders wished to avoid.

Regardless of one’s opinion of the Electoral College, even a cursory look at the formulation of our government shows that we are a republic, not a pure democracy. We are a union of 50 individual states, and the person elected to be our CEO needs to have a mandate from the states he oversees, not from a plurality of people in a few states.

The simple-majority will of the people is not supposed to be felt at the federal level except in one area: The House of Representatives. In the house, Representatives are elected by a democratic vote (a simple 51% majority) in each of the districts within the state. As such, the Rep works on behalf of the wishes of those people in those districts at the Federal level, so that the laws that are written and passed have the interests of the individuals in those districts.

Since the President is supposed to execute those laws (hence the name, Executive Branch), he has to be elected with both individual and state support. The Electoral College is the compromise of both. The INDIVIDUAL casts his ballot for whom he wants to be “the CEO of the union of the states, and executor of the laws his representatives write,” and the STATE sends electors to formally elect that state’s chosen candidate.

The person with the most votes based on the numbers assigned to the states wins the title as “Chief Executive and Person to Preside over the Union of the States,” or, “President of the United States of America.”

Now, of course there have been a few hiccups in the system since 1787, some of which have been corrected over time and some which haven’t. Originally the 2nd place person in the Electoral College vote became the Vice President. After the election of 1800 that was changed and now we have the “ticket” election where (according to history) the 2nd place person is the loser, doomed to a life of no responsibility, autobiographies full of half-truths, and million dollar speeches at universities. I kid.

And of course the system, to paraphrase Hamilton, is “not perfect, but it is excellent.” There have been a few…head scratching moments; For example the election of 1876, where Hayes lost the popular vote but won the Electoral College vote after great Republican disenfranchisement by Democrats in the South (No, really.). Also there was that little matter of the 2000 election, but let’s summarize that little doozy thusly: If the media doesn’t call it for Gore before the polls close in the Florida panhandle, W. wins Florida more clearly, wins the popular vote, there is no recount, and Al Gore becomes another in the long line of VPs who couldn’t win the top of the ticket. Like Hubert Humphrey (lost to Nixon). Or Gerald Ford (lost to gravity).

The United States of America is a republic, not a democracy. The will of the people is respected through the prism of the states of which they are citizens.

The states, via the voting of the citizens of the states, are assigned a number conducive to the population of the state, but weighted so that a simple majority of “large states” is not enough to win the election; the candidate must campaign on issues that affect a plurality of states (each distinct in size, culture, regional bias, traditions, etc).

Alas, the founders, to their fault, were not able to see the future. They did not anticipate at first the physical growth of America (from sea to shining sea) and then the social-shrinking of America (via mass media, the automobile, the internet, etc).

The former meant that the regional biases, which in the beginning was limited to “North v South,” would grow into multiple regional biases (Left Coast, Mountain West, Bible Belt, Rust Belt, New England), each still having states that have their own cultures, but also all having an overall regional culture—one different from the other—so that no one candidate can possibly appeal to all of them at the same time.

The latter meant that the lines of distinction between the states, with their rich traditions and history would slowly fade with each successive generation. Which is what we’re seeing now.

Few Americans can name one of their state senators (those elected to serve in their state houses), but they can likely name at least one of their two US Senators (who represent their state in the US Capital). That’s something else the founders did not anticipate.

It’s why the 17th amendment made sense (and still does today, unfortunately) in 1911. Because, while the founders expected us to be more involved in our local civic affairs, and to actually think about who would represent us in our STATE legislatures (which was very important to them), we, the general population of the US actually stopped caring (and there’s evidence that we hardly ever started). So the idea that we should personally elect our US Senators made sense. But it should never have NEEDED to make sense. If I cared enough to vote for my STATE Senator, then I would be able to trust that my STATE Legislature would appoint the FEDERAL Senator that best served the interests of my STATE (which is the Senators job).

We’ve gotten away from thinking of ourselves as citizens of our state, and instead we are just citizens of “the nation.” This is totally counter to the Constitutional Convention’s intention.

And despite popular thinking, every voter’s vote does count. To the same extent (but in a different way) that it would in a popular election for President. The reason a person in Arkansas says “My vote didn’t matter in 2016” is because the majority of people in Arkansas supported Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton. But that’s…A POPULAR MAJORITY! Now if enough of those voters were undecided (as was the case in a state like North Carolina or New Hampshire), then those voters would have gotten a deluge of advertising, campaign rallies and other events intending to sway their undecided vote.

So absolutely every vote counts, it’s just that some live in a state where the majority of citizens usually make up their mind early on. If a liberal in Arkansas disagrees with the majority opinion in his state, then what is he doing wishing for a popular majority election! At least with the Electoral College you could move to a state that is more in line with your culture. Where you gonna move if your preferred candidate loses a popular majority national election? This time Hillary won it, but next time it might be a republican that wins it and loses the electoral college vote. The tables always end up turning in American Politics.

As for the conspiracy theories about the electors, portrayed as mysterious people who flutter into smoke filled rooms and decide who the President is going to be…that’s ludicrous, and totally misconstrues the reality of what an “elector” is.

Put simply, these are the most trustworthy (bigwig) people of the political parties who represent the state in the formal electing of that state’s desired candidate for President. So if Arkansas’ citizens cast a popular majority vote in favor of Donald Trump being “the CEO over Arkansas’ union with the other 49 states,” then the GOP-appointed electors will convene to make Arkansas’ vote for Donald Trump formal.

It is basically a formality. Occasionally there will be a “faithless elector” who casts a different ballot than the wishes of the state (and there have been a few to threaten that this year), but most states have laws against this, and most often it is an inconsequential mistake, as in 2004, when a Democrat Minnesota elector cast a vote for John Edwards for President, instead of John Kerry. The state still went for Kerry because one electoral vote was not enough to sway the election. Should enough electors become faithless (as many Democrats hope this year), the electoral process would simply move to the House of Representatives and they would cast the ballot. In the end, the system has enough fail-safes that it will do its job.

Many Hillary Clinton supporters feel disenfranchised because more individual people voted for their candidate than Donald Trump, and yet Trump will be the next President. I understand the frustration but we have to respect the system that was put in place and the reasons it was put there. We are not a 300 million-people democracy, we are a republican union of 50 states who individually (as individual states) elect the one who will preside over that union.

As the founders intended.